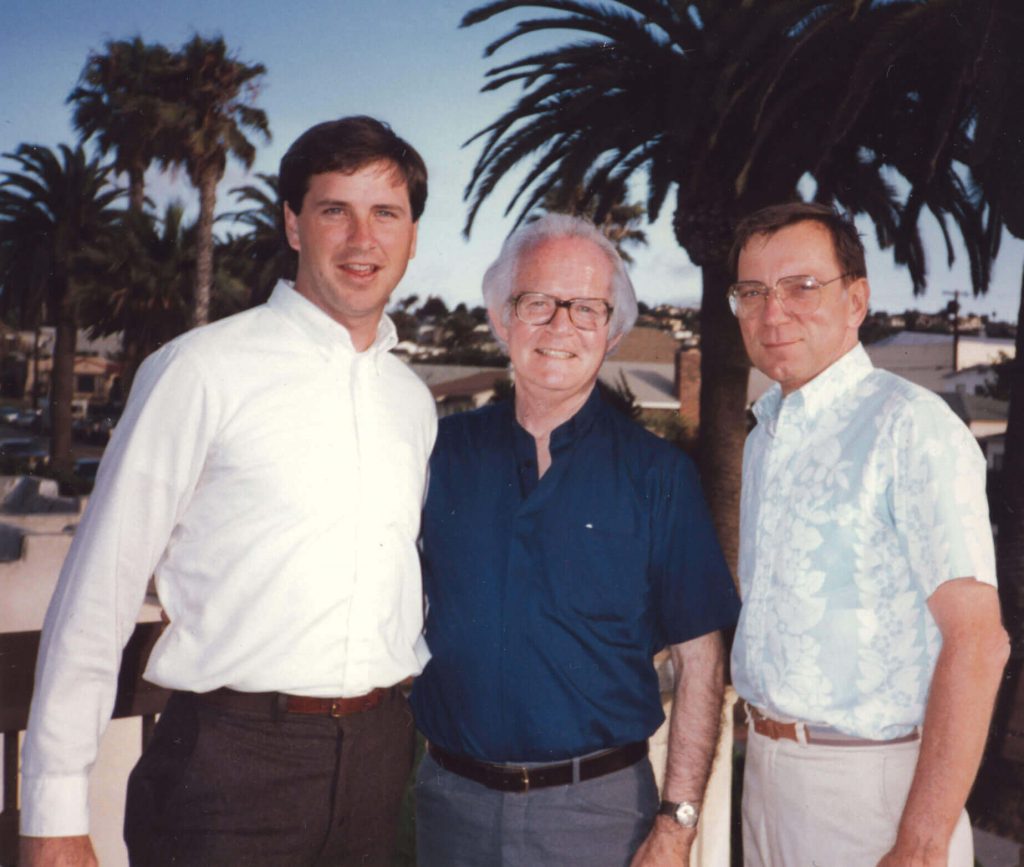

SAN DIEGO — In some families, Huntington’s disease (HD) can be traced back through generations, said Dr. Kenneth P. Serbin, a history professor at the University of San Diego. But for others, like his own family, the diagnosis comes as a complete surprise.

“It’s a devastating disease … and it doesn’t have any effective treatment right now,” Serbin said of the genetic neurological disorder, whose symptoms include involuntary movements; the loss of cognitive functions, including the ability to think and speak; and psychiatric and behavioral problems, such as depression, aggressiveness, hallucinations and suicidal tendencies.

After learning about his late mother’s diagnosis with the disease on Dec. 26, 1995, Serbin knew that he had a 50-percent chance of carrying the same defective gene that causes the disease. In 1999, he tested positive for it.

The symptoms of Huntington’s disease are so terrifying, Serbin said, that those who have it often will “just hide and not want to talk about the disease,” which currently affects about 1 million people worldwide.

“When you find out that you have Huntington’s or the risk of Huntington’s,” he said, “a lot of people begin thinking, ‘Well, who’s going to date me? If I carry this gene, who will want to marry me? Who will want to face having a child with me?’”

He said that, historically, affected persons have also faced discrimination and persecution. For instance, they were targeted for extermination in Nazi Germany; in the United States, in the mid-20th century, some in the medical community recommended that they be sterilized.

Even today, Serbin said, many people will conceal the fact that they have the disease or are likely to be affected for fear that they might lose their health insurance or that their employers might doubt their abilities.

“I was in what I call the terrible and lonely ‘Huntington’s closet’ until the year 2012,” said Serbin, who joined a support group shortly after his mother’s diagnosis and has been blogging about the disease since 2005, albeit anonymously for the first seven years.

But five years ago, he wrote an article titled “Racing Against the Genetic Clock,” which was published in The Chronicle of Higher Education.

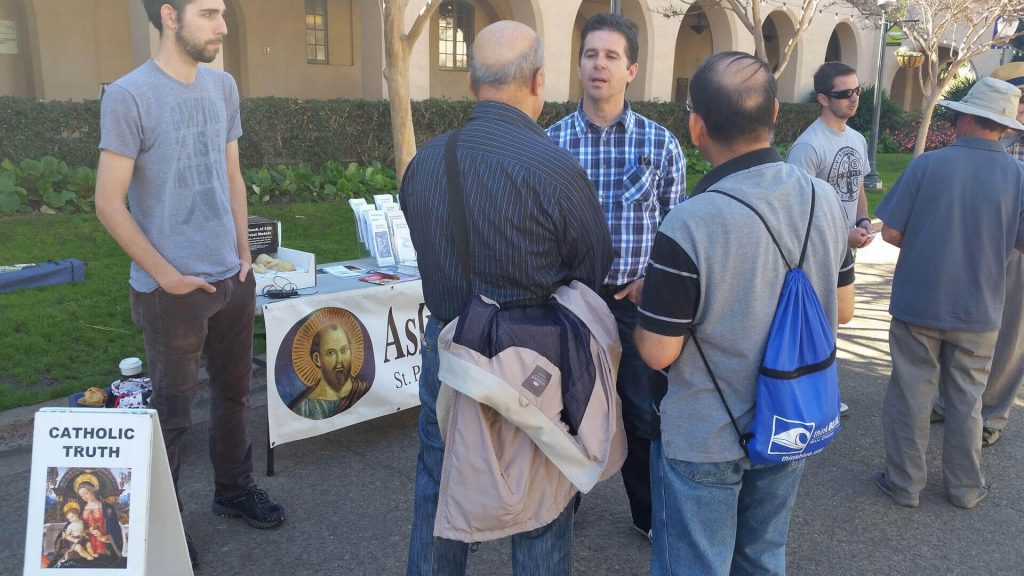

“With that article, I came out to the world,” Serbin said, explaining that his disease previously had been a closely guarded secret to which even his USD colleagues had not been privy.

Though he received a positive response to the revelation, he concedes that doing so exposes him to certain dangers.

“I’m here at USD and hope to stay here until I retire,” he said, “but what happens if … my wife gets a job somewhere else and we need to move somewhere? What will happen if I need to find another job?”

Serbin took the risk because he wanted to be a more effective advocate and hoped that going public about his illness would give others the courage to do the same.

On May 18, Serbin was one of an estimated 1,500 people, including Huntington’s disease patients, healthcare workers and scientists, who attended HDdennomore, a special papal audience held in the Vatican’s Paul VI Audience Hall.

Serbin said attendees were energized by Pope Francis’ speech, in which he declared that the oft-stigmatized disease should be “hidden no more,” and they left with the sense that their community was truly being “embraced by the Church.”

Following the speech, Serbin said, the pope spent almost an hour greeting attendees.

“When he came through the crowd, it was like an electric charge,” said Serbin, who was there with his wife, daughter and mother-in-law. “My tears were welling up in my eyes. A woman in front of me … practically fainted.”

During his own brief face-to-face encounter with Pope Francis, Serbin expressed gratitude for the pope’s support of the Huntington’s disease community, and he gave the pope a photo of his parents as well as copies of two books he has written about the Catholic Church in Brazil.

Serbin said the historic meeting at the Vatican is already bearing fruit.

“To my knowledge, in the more than 20 years I’ve been involved with Huntington’s disease, this is the most media attention I’ve ever seen,” he said, referring to news coverage of the event. “I think the immediate impact will be to make the disease ‘hidden no more’ and to start breaking down those barriers of stigma.”

He expressed hope that affected persons might be inspired by the pope’s words to come out of hiding and participate in clinical trials, join support groups or find other ways to contribute toward an eventual cure.

“My hope is that this will just raise overall awareness, not just about Huntington’s but other rare diseases and other neurological diseases,” Serbin said, and “that the world [will] be more caring in general towards people suffering from diseases.”